This is the fiercest burrito we have ever seen!

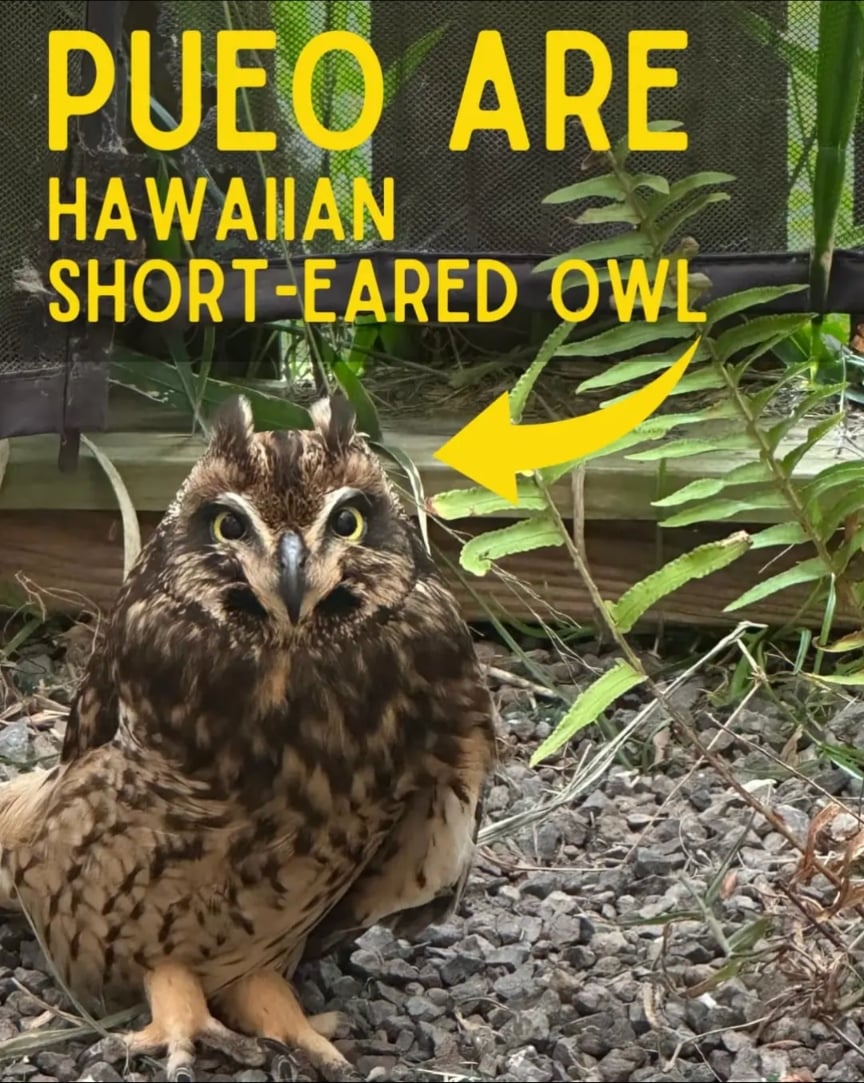

The Pueo is Hawaii’s only native owl. It’s a type of Short Eared Owl.

Welcome to Freebirds!

That’s one heck of a burrito! 😮🤤

Here’s an adult for reference:

I was in a band called Fierce Burrito. Mostly punk and metal, and all our lyrics were about asses.

all our lyrics were about asses

The animal, the body part or both?

The body part of the animal.

I would listen to that. 😆

Hawaii has one other owl:

The Barn Owl was brought in by the Board of Agriculture and Forestry from 1958-1963 to eat rats in the sugarcane fields. The Barn Owls are generalist predators, eating near any meaty things they can catch, so they have been a massive success and have spread all across the islands.

No evidence exists showing they did anything to resolve the rat issue though! 😧

“Mmrph . . when I get outta here . . nnrhgh . . you are so bit!”

Yeah! That’s for the burrito thing! Now lemme outta here!

Someone shared the AI suggestions, which I thought were funny in context.

Now that they mention it, I would like step-by-step instructions on how a Fierce Burrito is made

Does one have to be very careful when handling owls (or bird in general)? I imagine their bones are quite brittle, but when I try to break a chicken leg, it’s actually quite tough. Hens and roosters don’t fly though and I’m guessing their bone density is a major factor.

Hens and roosters don’t fly

That isn’t completely true. The wild ancestors of our chickens needed flight as part of their survival strategy.

The different breeds of chicken that still exist today have varying degrees of ability. In general they aren’t good or persistent fliers. Of course humans are at fault. They kept and bred chicken for meat and egg production. That’s why chicken mostly kept or developed even bigger muscles but their wingspan didn’t keep up with their body weight. Smaller breeds with regular feathers can fly a short distance and reach a height of about 9 to 10 meters. That’s why my grandfather regularly clipped the wings of his chickens and still had a high fence surrounding the area he kept them in. The chickens were still able to fly up into the small bushes and trees.

And more learned today! Thank You! :)

Many parts of bird’ physiology are very different than our own, and birds can easily be injured or killed if handled improperly. One of the big warnings for people attempting to rescue birds they find is not to give them anything to eat or drink. The main reasons for this is that their throats are set up differently than ours, as water can more readily go to their lungs than it would for us, and giving them any food, what you feed them may be incompatible with their digestion, such as feeding seeds to a carnivore or the other way around, and also, if the bird needs to be anesthetized once professional help gets them, it can cause them to throw up and have stomach contents go into their lungs (aspiration).

If people are handling most wild birds, it is due to them being sick or injured. Before they can be checked for what exactly is wrong with them, the handlers don’t know what movements could make injuries worse. If there is a broken bone, having the bird panic and flail could cause a bone to go through the skin or muscle, making the injury worse, for example. Feather damage is also no joke for a wild bird. If feather shafts are broken, they may not be able to fly for up to a year until they molt those feathers. They can also get injured by trying to get away, by the handler’s resistance or by hitting other things, or just bending the wrong way while being held. Or they could always injure the rescuer as well. Having them restrained can help calm them and avoid causing new injuries to anyone involved.

I found a Raptor Rehabilitation Guide that lists some other potential hazards involved in handling and rescue. I’ll copy here the things related to avoiding injuries.

Handling raptors

Correct handling of birds minimises the risk of harm to both birds and handlers. Before handling a bird, identify its most dangerous features and gain control of these first. The main defence mechanism of raptors is their talons. Birds that appear to be calm can strike without warning and aggressive raptors can flip onto their backs and strike out with their feet. Falcons often make sudden attempts to escape and ruru (moreporks) can inflict painful scratches.

To pick up a raptor from a cage or box, start by draping a towel over the bird when it is facing away from you. Then gently push the bird to the ground and grasp the legs from behind and beneath the tail. Care must be taken not to squeeze the legs together. When the legs are under control, lean the bird’s back against your abdomen, with your other hand free to restrain the head if required. Keeping the head covered with a towel will help to calm it. The towel can be used to wrap around the bird’s wings in a swaddling wrap while it is being handled. When handling birds, always ensure that any restraint around the chest is loose enough that the bird can still easily move it to breath. A novice handler will require a second person to assist when handling raptors.

Hospital cages

Cages used for housing critically sick and debilitated birds are referred to as ‘hospital cages’. They securely hold birds and encourage them to rest quietly whilst allowing effective monitoring and treatment.

All large raptors should have a tail wrap to protect their tail feathers from damage in hospital cages. Insert the tail into a suitably sized clear plastic bag and staple the bag to hold the tail in place. Do not staple the central shaft (rachis) of the feathers and ensure the vent (where the bird defecates from) is excluded from the wrap. Remove the wrap when the bird is transferred to an aviary.

Cages should allow for provision of supplementary heat via a warm room, heat pad or hot water bottle wrapped in a towel.

Provide suitable substrate on the floor of the cage to prevent foot abrasions. Towels or easily cleaned soft rubber matting are good options. Newspaper can be quite slippery for raptors and can only be used along with towels, perches or matting. Avoid use of materials with rips, frayed edges or holes, which may entangle feet.

Cover transparent doors or whole wire cages with towels or cloth to give some privacy and to prevent attempts to escape which may incur further injury. Allow some natural light to enter the cage to encourage feeding.

The question about bone strength is a really good one, and having to read up to answer this actually cleared up a few of my own misconceptions and has been very informative.

So, I found this research paper, Bone density and the lightweight skeletons of birds, Dumont, 17 Mar 2010, and it revealed some critical details. Bird bones are actually composed of denser bone than mammalian bones. While they are hollow, the material is less porous and more mineral rich. While thin walled and hollow, there are internal structures that add rigidity. The forces involved in flight and landing cause rotational stress, and this hollow structure resists twisting forces better than our more solid bone structure. Mammalian bones having a bit of give lets them flex to avoid injury. Here is a dog femur vs a chicken femur for comparison:

If bird skeletons were the size of mammal skeletons, the bird’s would be the same mass or even heavier. One key thing though, is birds are not built like us. We have relatively little padding, and are much more meat and bone for our size. Birds on the other hand, are mostly feathers and air sacs (very high oxygen requirements to fly!) loosely held together by bones. And their bones have one pretty big downside. Mammal bones break like a piece of standard glass, in a few big cracks. Bird bones break like tempered glass. It’s harder to break, but when it does, it shatters. This is why we aren’t supposed to give dogs poultry bones, as they make pokey splinters. It also becomes more difficult to repair that delicate matrix structure so it can heal. I think that is a pretty accurate summation of what was in the paper. There’s much more interesting stuff in there, but I don’t have a chance to read it fully now.

I came for the cute animal pictures, and stayed for the knowledge. Thank you for taking the time to write all that.

I try to satisfy those that just come here for cute pictures, but they’re such amazing creatures, there is so much knowledge to share about them!

We enjoy humanizing them for their fun faces, but they are so different from us in so many ways. It makes them full of fun surprises to share with you all!

Thank you! I learned more about birds today than I ever have 🙂 Ahhh, if I had the time and money, I’d volunteer at rescue to learn more about them.

Have a good one!

What an Owl Knows by Jennifer Ackerman is a great book if you want to learn a lot in digestible, easy to understand language.

Also, don’t hesitate to find a rescue/rehab near you and go look and ask questions. The people are all there because of their love for the animals, so they will talk your ears off if they aren’t too busy. I did a 50 States of Owls last year if you’re in the US, to show everyone there are lots of owl places to visit wherever you may be. Owls are in every place people are, so there are always some nearby.

You can also help local owl just by donating time, money, or supplies to your local rescue center. They always need paper towels, bedding, cleaners, and a ton of other basic supplies. No rehab I have come across in any country gets any tax money for their services, so it is all privately funded by people like us. I was even reading about someone helping from home raising grubs to feed to their local rescue animals so the place didn’t need to buy them.

There are tons of opportunities for anyone to participate, no matter how much or little they have to give at the moment!