The website Hodinkee reinvented watch culture, giving luxury timepieces the same air as a pair of rare Nikes. Now it faces a market downturn and accusations of mismanagement.

Ben Clymer, the founder of the watch website Hodinkee, is the closest thing that the wonky watch world has to a celebrity—the sort of guy collectors would stop on the street to take a selfie with. His personal Instagram is peppered with gold watches, vintage Porsches and photos with celebrities like Lenny Kravitz.

A former project manager at UBS, in 2008, Clymer turned his passion for watches into a chatty blog where he could spotlight watchmakers and opine on the latest Omegas. The site blossomed over its first decade. It published a glossy print magazine and launched a successful YouTube series featuring famous watch collectors like Kevin Hart, Aziz Ansari and Andre Iguodala. Soon, Hodinkee was hosting champagne-filled parties with Omega and collaborating with John Mayer on collectible watches that sold out with the speed of rare Nikes.

By 2020, Clymer had said Hodinkee was generating around $25 million through ad sales, events, a watch insurance program and a small online shop. The next stage was driven by a question: Would people who read about $50,000 watches on Hodinkee buy them there, too?

When online luxury shopping boomed amid the pandemic, Hodinkee rode the wave, pocketing $40 million from investors including Mayer, LVMH Luxury Ventures, the Chernin Group and Tom Brady. At that point, Clymer said, the company was turning a profit and the investors valued it at more than $100 million. In February 2021, it acquired Atlanta watch resale company Crown & Caliber as prices on the secondary market began steadily climbing to record heights. Hodinkee was looking for a way in.

“I don’t want to say we were chasing it,” said Clymer, during an interview in Hodinkee’s Manhattan office last month. “But again, we’re looking out the window and I see it’s sunny, I’m not going to put on a raincoat. It’s no different than that. We saw what was happening in the market and we went for it.” In December 2021, the company set a goal of $141 million in revenue, according to a board presentation.

Then, in early 2022, the rains came.

Prices of pre-owned watches started declining: After hitting a peak in March 2022, they fell nearly 30% by the end of that year, according to the WatchCharts Overall Market Index, which tracks resale prices over 60 high-end timepieces. It has since only dipped further. Resale prices of some high-end watches are about half what they were just two years ago. The decline in interest has crashed into the broader industry—shares of certain luxury watch businesses have plummeted this year, shedding as much as half their value.

Now Hodinkee is an example of how precarious luxury investments often are at a time when trends whipsaw faster than ever. It also shows how the pandemic made many investors overconfident about the promise of online retail and how, years later, they are dealing with the resulting hangover.

“All of us took some form of a bath on some watches at one point,” said Jeff Fowler, Hodinkee’s chief executive, during the interview last month.

Hodinkee’s growth strategy now appears ill-timed. Sixteen former employees paint a picture of a company that is running out of time to turn itself around. For years, Hodinkee has been plagued by overspending and projects that failed to launch, according to the former employees, many of whom left within the last year or so. Former employees said that the company had five rounds of layoffs over 18 months. Its staff today hovers around 50, down from a peak of roughly 160 people, according to Hodinkee.

Revenue at the company has declined to around $70 million last year from around $100 million in 2021, according to former employees familiar with the company’s finances. It also hasn’t been profitable for the past few years, according to former employees.

A downtown Manhattan retail location that is currently plastered in Hodinkee branding has sat dormant since Hodinkee signed a lease for the space in 2019. According to a former employee familiar with the company’s finances, it eventually cost Hodinkee as much as $80,000 a month. The company says it’s planning to sublet the space to a new tenant this summer.

To Clymer and Fowler, Hodinkee’s pullback is better situated for growth at its shrunken scale.

“The business is stronger than it’s ever been,” Clymer said about the downsized company. “I believe in this business now more than ever.”

Positioning for Growth

When Hodinkee announced $40 million in investment in December 2020, Clymer stepped down as chief executive, passing the reins to Toby Bateman, the former managing director of online menswear retailer Mr Porter. Clymer stayed on as executive chairman and described his current role as “the emotional leader of the business.”

Within months, Hodinkee acquired Crown & Caliber, then an 8-year-old pre-owned watch reseller. They paid around $46 million for the company, according to a former employee with knowledge of the deal.

Crown & Caliber knew how to purchase bundles of high-end watches, photograph them, list them and ship them out to buyers. Hodinkee knew how to attract an audience. On paper, the combination seemed like a good fit.

In the year before the acquisition, Crown & Caliber was bringing in $53.6 million in revenue, roughly two times that of Hodinkee, according to a financial report reviewed by the Wall Street Journal.

“In 2021, pre-owned was everything,” said Clymer.

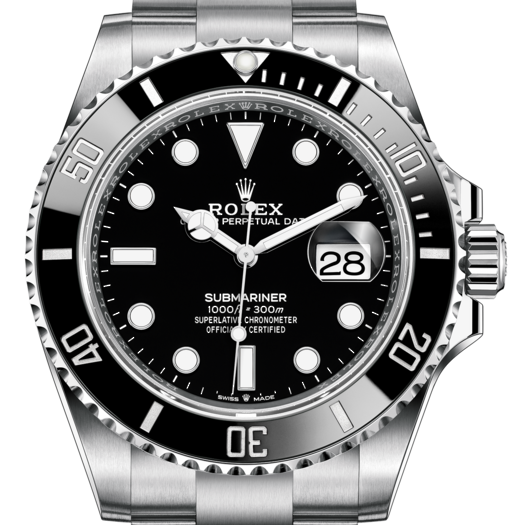

Crown & Caliber’s success was driven in part by the way watch companies, most notably Rolex, limit the number of watches they release in a given year. If shoppers want, say, a Rolex Daytona or an Omega Speedmaster, they can’t just walk into a store and buy one. Wait lists for certain watches can stretch into years. To skip the line, many shoppers are willing to spend more with pre-owned resellers such as Crown & Caliber.

“Hodinkee had an incredibly strong brand, we still do,” said Clymer. “But what we weren’t great at was fulfillment and returns and things like that that actually really drive a business.”

But almost immediately, former employees said, problems with merging the two companies cropped up.

Crown & Caliber customers were often horological novices who wanted a nice watch to mark a life milestone. The Hodinkee reader was a watch enthusiast, who might already have a safe full of rare Patek Philippes and wasn’t necessarily in the market for a used Rolex. The idealized scenario in which Hodinkee readers crept over to Crown & Caliber’s pre-owned offerings just didn’t seem to be happening, said former employees.

There were logistical issues, too. Former employees said that it was a longstanding goal to fold Crown & Caliber into Hodinkee. Yet the company didn’t sufficiently prepare to consolidate the two websites, which operated on two separate back-end systems, former employees said. That made it difficult to manage inventory and fulfill orders across the two companies.

“With any merger, it can take years to fully integrate a team,” Clymer said in a statement.

Crown & Caliber employees grew resentful that Hodinkee, a less profitable but showier company, had acquired their workplace, said several former employees.

Fowler acknowledged that merging the two corporate cultures—the unsexy warehouse-based team in Atlanta and with the slick, public-facing team in New York—was a challenge. “I heard, ‘Us, them.’ ‘Atlanta, New York,’” Fowler said about conversations he had with employees when he joined.

Clymer and Fowler initially denied planning to shutter the site. When asked about a board presentation reviewed by The Wall Street Journal that indicated that had been the plan, Clymer responded, “Things change.”

Meanwhile, Bateman, the new CEO, was in his native England, and traveling to the states was a struggle due to Covid restrictions. After less than a year-and-a-half, he was out. In March 2022, the company had a new CEO: Fowler, the former American president of online luxury retailer Farfetch.

The Market Turns

In the middle of 2022, the watch reselling market turned. Hodinkee felt it immediately.

Suddenly, watches like the Rolex Daytona, which sold for around $45,000 in March, were fetching as much as $10,000 less in June. The company scrambled to stanch the bleeding. At first it ceased procuring specific models, including Rolex sport watches, then ultimately stopped purchasing watches altogether, adopting a trade-in-only model.

“We implemented pretty firm guardrails to avoid the problem ballooning for us,” Fowler said.

When the dust settled, Hodinkee amassed roughly $2 million worth of pre-owned Rolexes above their market value at that time, according to former employees.

To boost sales, Hodinkee started to clear out inventory by increasing the volume of promotions, former employees said. Clymer and Fowler dispute that.

By December of last year, the inventory, which in healthier years could be well into the thousands, slumped to below 300 watches as Hodinkee had less money to spend on new watches to resell, according to a former employee with knowledge of the stock. Today there are around 850 pre-owned watches available on Crown & Caliber’s website.

“We definitely had to manage cash closely through a period of time,” Fowler said, adding that the diminished inventory is “a definite conscious decision.”

What’s more, sellers were not getting paid for weeks, leading to customer service complaints and outcry on forums like Reddit about delayed payments, said those that left the company in late 2023 or early 2024.

Fowler disputed this, saying, “I don’t think we ever had any obligations that we didn’t fulfill.”

The Pivot

Over the past 18 months, Hodinkee has been cutting jobs across all facets of its business, according to former employees. The VIP sales team, a crucial wing of any luxury retailer servicing big-spending clients, has been gutted. Watchmakers in Atlanta, who approved and serviced watches that the company resold, were let go. Just a few years after the acquisition, only 14 employees are left in Atlanta.

“No one enjoys going through these types of changes,” Fowler said. “But a reorganization was necessary to ensure the business was put onto a more sustainable path financially.”

F ormer employees said the dwindling workforce created some big problems. Last October, Hodinkee’s editorial website went down on a critical sales day because the employee whose corporate credit card was tied to the site’s hosting fee had been let go months before.

Former employees also said that a planned eBay-style marketplace, once highly touted internally as a way to spare Hodinkee from holding a risky amount of inventory, was tabled and several former employees who worked on it were let go.

While the company’s editorial staff still publishes a handful of stories a day, past employees said that customers were growing bored of the limited-edition watches that used to sell out as fast as a pair of coveted Air Jordans.

A launch last year of a G-Shock ref. 6900 with British singer Ed Sheeran languished in the warehouse, according to former employees. Several former employees said that the company began to mark limited-edition watches as “sold out” even if stock was still available.

Clymer disputed that description and said he wasn’t concerned about the speed at which the limited-edition products sell out. “Sometimes stuff takes, you know, 10 days instead of 10 minutes,” said Clymer, “But you know that’s okay with us.”

Never heard of mine.